We may earn a commission when you purchase through affiliate links. Learn more.

Both RAW and Jpeg file formats have their uses and in this guide we’ll take a look at what each format offers and when it would be the ideal choice for your photography.

The sensor in your digital camera records light information from tiny photosites, often simply called pixels. All this data requires processing to produce a photo, and when shooting JPEG, the camera firmware applies built-in presets, adjusting many things like saturation and contrast automatically, before compressing the image and leaving you with a JPEG file that can be uploaded to the web or printed moments after you’ve taken it. All of the additional information which the camera didn’t make use of is discarded when shooting JPEG.

When you shoot in RAW, the sensor data is preserved in a much larger file and the camera doesn’t apply its internal processing algorithms – producing an image that tends to look rather flat, but contains a great deal of tonal information. To actually view your full-size photo off the camera (when you shoot in RAW the camera still generates a small JPEG so that you can preview the image on the screen), you’ll need a computer with software capable of viewing and then processing RAW files. Although the files produced are much larger, if you plan to do any post-processing to your images, RAW is by far the superior choice.

What is Dynamic Range?

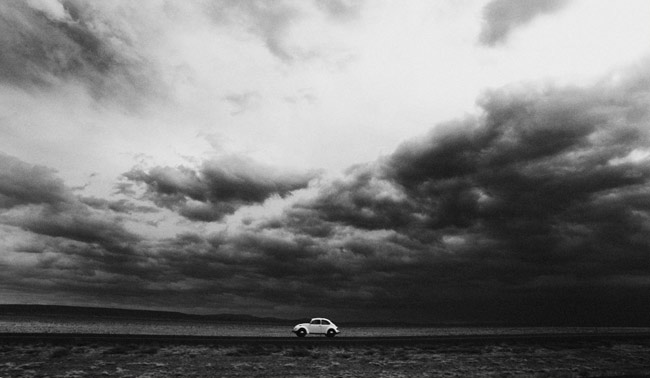

You will often hear the term Dynamic Range used when people are debating whether you should use RAW or JPEG. Dynamic range refers to the sensitivity range of a digital camera sensor, quantifying the range between the brightest and darkest details that can be recorded. As you can probably guess, the dynamic range of RAW files is much higher than in JPEG files, since more information is preserved. This means that if you shoot RAW, not only can you make adjustments to basic settings like white balance, vibrance, saturation, brightness, and contrast, but you can even recover details that would have been lost in the shadows and highlights of the photo.

If RAW Is So Great, Why Do So Many People Shoot JPEG?

One reason is that JPEG is easy and small. Just like the Auto setting on your camera, shooting in JPEG is simple and you can share a photo online or print it right after you’ve taken it, even if you don’t have any editing software or apps. Because JPEG files are smaller than RAW files, you can also fit more of them on a memory card, although this is a less compelling reason these days since the cost of storage media is very low. Because of their small file size, JPEG images can also be written to and read from the memory card much quicker; this means that you can shoot more JPEG images in a row (burst shooting) without your camera pausing for a few moments after the buffer is filled. You can also load them onto your computer more quickly.

Situations where you need to print the images immediately (like a party where the guests get a photo to take home) might be another good time to shoot in JPEG if you’re very confident in your photography skills.

While the benefits of JPEG are mainly small size and simplicity, shooting in RAW is of great benefit to the serious photographer, even allowing a significant amount of tonal detail to be recovered in images that are over or underexposed. It’s important to remember that shooting in RAW alone won’t give you a great photo — even the best photo needs to be processed well for it to look great, and learning to process your RAW files well to extract as much detail as possible is something that takes lots of practice. To process the files, you’re going to need some software on your computer to do this.

If you’re just starting out in photography, it’s a great idea to start shooting RAW. We all make mistakes — even after years of experience, and having a RAW file allows you a greater level of mistake forgiveness, letting you recover lost detail in shadows and highlights that would be gone forever had you only shot a JPEG image.

RAW + JPEG — The Best of Both Worlds?

If you like the simplicity of being able to share some of your photos right away, but still want the option to go back later and process them differently, most mirrorless and DSLR cameras and even some newer compact digital cameras allow you to shoot both RAW+JPEG. A handy tool for the times when you need it, you’re better off not using it all the time since it uses double the number of files written to your memory card and can create more hassle than its worth if you don’t really need both all the time.

Processing RAW Files

Most cameras come with some kind of RAW processing software included in the box. Some of this software is better than others and doesn’t really integrate into a post-processing workflow very well, so many photographers choose to use popular third party software like Adobe Lightroom, Adobe Photoshop, or Affinity Photo. Generally the automatic settings for RAW processing using these software programs will be pretty good, but they allow you to modify many settings like exposure, white balance, contrast, vibrance and saturation, noise reduction, and sharpness to your own liking allowing you to create a truly unique image that looks exactly the way you want it to.

Free RAW Processing Software

While you may want to shoot in RAW, you might not want to invest any money in software, especially after stretching your budget with a camera purchase. Fortunately, there are a few free options for RAW processing!

Darktable – Of use to Mac and Linux users, Darktable is an open source photography workflow application and RAW developer offering a virtual lighttable and darkroom for photographers. It manages your digital negatives in a database, lets you view them through a zoomable lighttable and enables you to develop raw images and enhance them.

RAW Therapee – An open source RAW processor that works on Windows, Linux and Mac OSX, RAW Therapee offers desirable features like batch processing and parallel editing of multiple images.